In the first hours of his presidency, Donald Trump signed Executive Order 14149, “Restoring Freedom of Speech and Ending Federal Censorship.” The Order prohibits any “federal department, agency, entity, officer, employee, or agent” from acting “in a manner that advanced the Government’s preferred narrative about significant matters of public debate.”

Two days later, the new chairman of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) reopened a previously dismissed proceeding, the effect of which was to advance a Trump campaign “preferred narrative” about the CBS television network. The action not only inserted the agency into matters of freedom of speech but also the personal lawsuit brought by private citizen Trump against CBS.

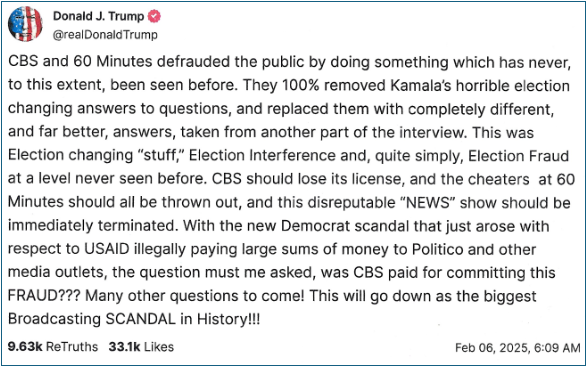

The FCC sent CBS a “Letter of Inquiry” requesting an unedited transcript of a “60 Minutes” interview with presidential candidate Kamala Harris. The Trump campaign had claimed CBS manipulated the interview to candidate Harris’ advantage. On February 5, the FCC created an official docket on the CBS investigation. The next day, President Trump took to Truth Social to rail against CBS and to call for cancellation of CBS’ broadcasting licenses.

Two days following the opening of the FCC docket, Donald Trump—acting as a private citizen—doubled the size of the damage claim from $10 billion to $20 billion by including CBS parent Paramount Global as a defendant.

Presidents have the right to express themselves—and frequently do—on matters before the FCC. Unlike a cabinet secretary, however, the chairman of the agency does not report to the president. The FCC is chartered by Congress as an independent agency, separate from the executive.

The president’s input that “CBS should lose its license” (an FCC decision) and its relationship to a lawsuit from which he could personally benefit is unusual. The New York Times headlined, “Paramount in Settlement Talks With Trump Over ‘60 Minutes’ Lawsuit.” The Times reported, “A settlement would be an extraordinary concession by a major U.S. media company to a sitting president, especially in a case in which there is no evidence that the network got the facts wrong or damaged the plaintiff’s reputation.”

Reporting on the CBS lawsuit, the Wall Street Journal explained, “Company executives in recent weeks have talked about the risk that paying such a settlement could expose directors and officers to liability in potential future shareholder litigation or criminal charges for bribing a public official.”

All of this occurs against the background of the sale of Paramount Global (and its CBS subsidiary) for $8 billion that was announced in July. Because CBS owns 28 television stations, the FCC must approve the transfer of their federal licenses to use the airwaves. As a result, the agency has tremendous leverage over the company.

Chairman Brendan Carr has linked the reinstated complaint with the FCC review of the license transfers: “I’m pretty confident that that news distortion complaint over the ’60 Minutes’ transcript is something that is likely to arise in the context of the FCC review of that transaction.”

This politicization of the FCC’s processes would appear to be in conflict with a 2021 statement issued by then-Commissioner Carr that said, “A newsroom’s decision about what stories to cover and how to frame them should be beyond the reach of any government official, not targeted by them.”

“Washington lobbyists say the Trump administration will use regulation to get what it wants from the media, including more favourable [sic] coverage, at a time when many groups are trying to strike new deals and are seeking consolidation,” the Financial Times reported. Some suggest there is an incestuous relationship between what Donald Trump the private citizen stands to gain monetarily and the leverage that President Trump has over the business goals of the companies regulated by the FCC.

The New York Times reports that Paramount is presently in settlement discussions. “[M]any executives at CBS’s parent company, Paramount, believe that settling the lawsuit would increase the odds that the Trump administration does not block or delay their planned multibillion-dollar merger with another company, according to several people with knowledge of the matter.”

The Trump suit against CBS isn’t his only suit against the major media outlets. Post-Election Day, the Walt Disney Company, which owns the ABC television network, settled a suit alleging ABC anchor George Stephanopoulos had defamed candidate Trump by saying on air that he had been found liable for “rape” in the E. Jean Carroll case. The jury’s terminology was “sexual abuse.” In the settlement, ABC agreed to pay $15 million to the future Trump presidential library.

Another post-election decision was Meta’s settlement of a Trump lawsuit alleging the violation of his First Amendment rights for deplatforming him after the Jan. 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riots. Meta agreed to pay $22 million to the future Trump library. Although outside of the FCC’s jurisdiction, it reflects a pattern of apparent appeasement to Trump’s censorship intentions.

The Communications Act of 1934 vests authority over the commercial use of the public’s airwaves in the FCC. The Commission’s policy manual explains, “In exchange for obtaining a valuable license to operate a broadcast station using the public airwaves, each radio and television licensee is required by law to operate its station in the ‘public interest, convenience and necessity.’ Generally, this means it must air programming that is responsive to the needs and problems of its local community of license.”

Under the heading “The FCC and Freedom of Speech,” the Commission manual explains, “The First Amendment, as well as Section 326 of the Communications Act, prohibits the Commission from censoring broadcast material and from interfering with freedom of expression in broadcasting. The Constitution’s protection of free speech includes programming that may be objectionable to many viewers or listeners. Therefore, the FCC cannot prevent the broadcast of any particular point of view. In this regard, the Commission has observed that ‘the public interest is best served by permitting free expression of views.’”

In October 2024, in the midst of the presidential campaign and shortly after the “60 Minutes” interview, the conservative Center for American Rights (CAR) filed a complaint with the FCC. The complaint argued that the editorial decisions of CBS “amount to deliberate news distortion—a violation of FCC rules governing broadcasters’ public interest obligations.”

Discussing that filing on Fox Business, then-commissioner Carr observed, “the news distortion rule is a very, very narrow rule at the FCC. In almost every case, it doesn’t apply because it could get into sort of editorial decisions that are protected by the First Amendment.” Nonetheless, he called on CBS to release the transcript of the interview.

The FCC has historically refused to act on news distortion claims because of concern over their First Amendment implications. Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel, Mr. Carr’s predecessor, dismissed the CAR complaint (along with several others) with the observation that the FCC shouldn’t be “the president’s speech police [and] should not be journalism’s censor-in-chief.” When Carr became chairman, he overturned Rosenworcel’s dismissals and reasserted FCC investigations into content complaints, except for one filed against a Fox-owned Philadelphia station.

There is ample legal precedent limiting the FCC’s ability to engage in curatorial content decisions. In New York Times v. United States (the 1971 Pentagon papers case), the Supreme Court ruled that even in issues of national security, government censorship had to clear a very high bar. In Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974), the Supreme Court held that government cannot force media to cover stories a certain way, even as a pretext to fairness or balance. In FCC v. League of Women Voters (1984) the Court struck down an FCC rule that banned public broadcasters from editorializing.

The power of the FCC chairman to interpret the vague public interest doctrine invites its politicization—and in the case of the Trump lawsuit, its potential for abuse in private matters. Simply rattling the chairman’s saber can have a chilling effect on editorial and business decisions.

“[A]t the end of the day, obviously there’s a statutory provision that prevents the FCC from engaging in censorship,” Chairman Carr told CNBC shortly after President-elect Trump announced his elevation to chairman. “I don’t want to be the speech police. But there is something that’s different about broadcasters than, say, podcasters, where you have to operate in a public interest. So right now, all I’m saying is maybe we should start a rulemaking to take a look at what that means.”

It is an important suggestion. The use of ill-defined government policy as a tool of political coercion is something that is historically associated with authoritarian governments.

Chairman Carr’s proposal to “start a rulemaking to take a look at what that means” should be pursued with all possible dispatch. Such a proceeding would begin with the chairman putting forth a proposed public interest standard definition, followed by a full and open public debate on the proposal and an FCC vote. This would not only help to eliminate the vagueness that plagues the chairman’s current interpretation but also identify how he would enforce the rules when applied to broadcasters that are much more one-sided in their support of Trump policies.

Exploiting vagueness in matters of speech is an invitation to the exploitation of rights. As Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in a 2015 Supreme Court decision, “The vagueness of a law can invite arbitrary power.”

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Meta is a general, unrestricted donor to the Brookings Institution. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions posted in this piece are solely those of the authors and are not influenced by any donation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Trump’s CBS lawsuit ties media freedom to FCC’s regulatory power

February 19, 2025